Digital, Spiritual and Cutting-Edge Medicine Has U.S. Army Veteran and Movie Star Back On The Road to Recovery

This article originally featured in the June 2018 issue of Homeland magazine and republished with permission.

Life in the movies isn’t always the Hollywood dream most people assume, the one with limousines, private jets, talk shows, magazine covers, adoring fans, and infinite fame and fortune. Even with fancy red-carpet premieres and media hoopla, not every star is always thrilled to be part of the show.

When the Strong Eagle Media feature film Citizen Soldier premiered in theatres to critical acclaim in August of 2016, the stars of the opening and final credits showed up in tuxedos, did the media interviews and celebrated the opening with the rest of the cast and crew. In this particular 90-minute, R-rated film however, the stars were American soldiers not actors and the scenes were not fiction, but rather actual, authentic war-time footage shot under live enemy fire by the helmet cameras of their comrades.

Citizen Soldier featured film footage from a Sept. 14, 2011 battle in Saygal Valley, one of the most dangerous parts of Afghanistan. It was shot from the point of view of a group of soldiers in the Oklahoma Army National Guard’s 45th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, a group known since World War II as the “Thunderbirds,” who were engaged in a fire-fight during Operation Brass-Monkey.

Because the operation was more of a nightmare and not everyone in their platoon survived the conflict, at least one of the film’s stars was not a big fan of that intimate and excruciating footage being shown on the big screen.

“First of all, I think I was pretty much against this movie from the start,” confides U.S. Army Sgt. 1st Class (Ret.) Martin Byrne, a native of Tucson, Ariz., in the movie’s behind-the-scenes promotional trailer. “But then there was a turning point, and I offered 100 percent support to this film. Being able to key in on the brotherhood of our men, being able to key in on how much we cared and loved each other. The way the production company put this together, it was just unbelievable.

“This isn’t just another Hollywood film, we didn’t have embedded reporters, it’s none of that stuff,” Byrne clarifies. “These are just some men in my platoon who were authorized to wear helmet cameras. That’s it. It turned into some sort of flick, that is going to save someone’s life. I don’t know whose life it is going to save, but it’s going to save someone’s life and I’m telling you it’s probably already saved mine.”

How could a real-life war film have an impact on saving someone’s life?

According to David Salzberg in the film promo, some service members can find a film such as this one he directed with Christian Tureaud to be a worthwhile and powerful prescription for healing a variety of emotional wounds.

“The films become a living, breathing thing that honor the fallen heroes, that bring closure to the folks that were there,” says Salzberg, “that they’ve branded digital medicine.”

“Digital Medicine” is just one of several treatments Byrne has experienced since medically retiring from the U.S. Army National Guard in May 2014 after serving 16 and a half years in the military.

While Byrne left the Army with a Purple Heart, Bronze Star and numerous meritorious service, commendation and achievement medals, he also accumulated life-altering physical injuries, as well as challenges related to TBI (traumatic brain injury) and PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) issues.

Byrne enlisted in the Army in December of 1997 and stayed mostly out of harm’s way until moving to the National Guard in 2003 and undergoing multiple deployments to the Middle East as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. On Aug. 18, 2011, about one month before the film footage was shot in Operation Brass-Monkey, he suffered severe injuries when the vehicle he was the turret gunner on was blasted with a rocket propelled grenade (RPG). He was knocked unconscious, suffered multiple shrapnel wounds to his left side, broke his left arm and was medevaced out to a nearby combat trauma clinic in Jalalabad.

Much like a football player injured in the Super Bowl, he put some tape on it and went back out into the fight. Actually, despite being targeted for transfer to Germany for more extensive medical care, he decided to stick with his platoon a while longer, hiding the knuckles-to-armpit cast on his left arm under his uniform so his injuries would go unnoticed by the enemy. He remained in Najil, Afghanistan for more than six months before his body began to break down. He was then transferred for more extensive medical treatment to Camp Shelby, Miss., and later to his final post in Fort Riley, Kansas.

Since returning to civilian life in Wichita, Kansas, with his wife Alma and 10-year-old son Austin, Byrne has been involved in an exhaustive search for more effective treatments to his numerous physical and emotional ailments.

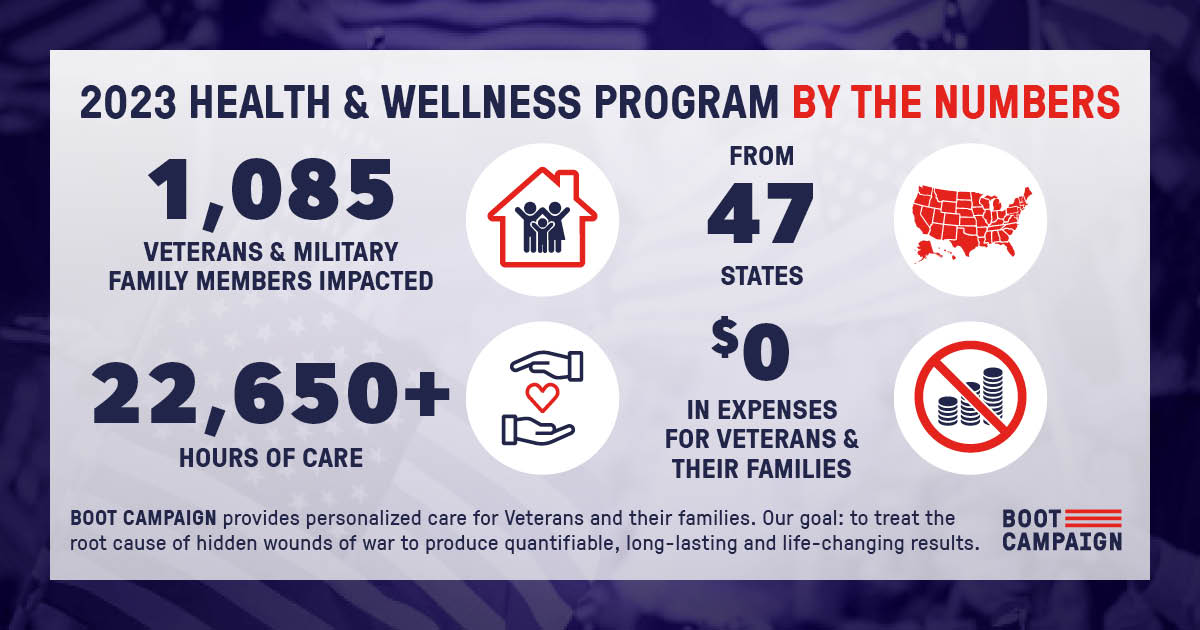

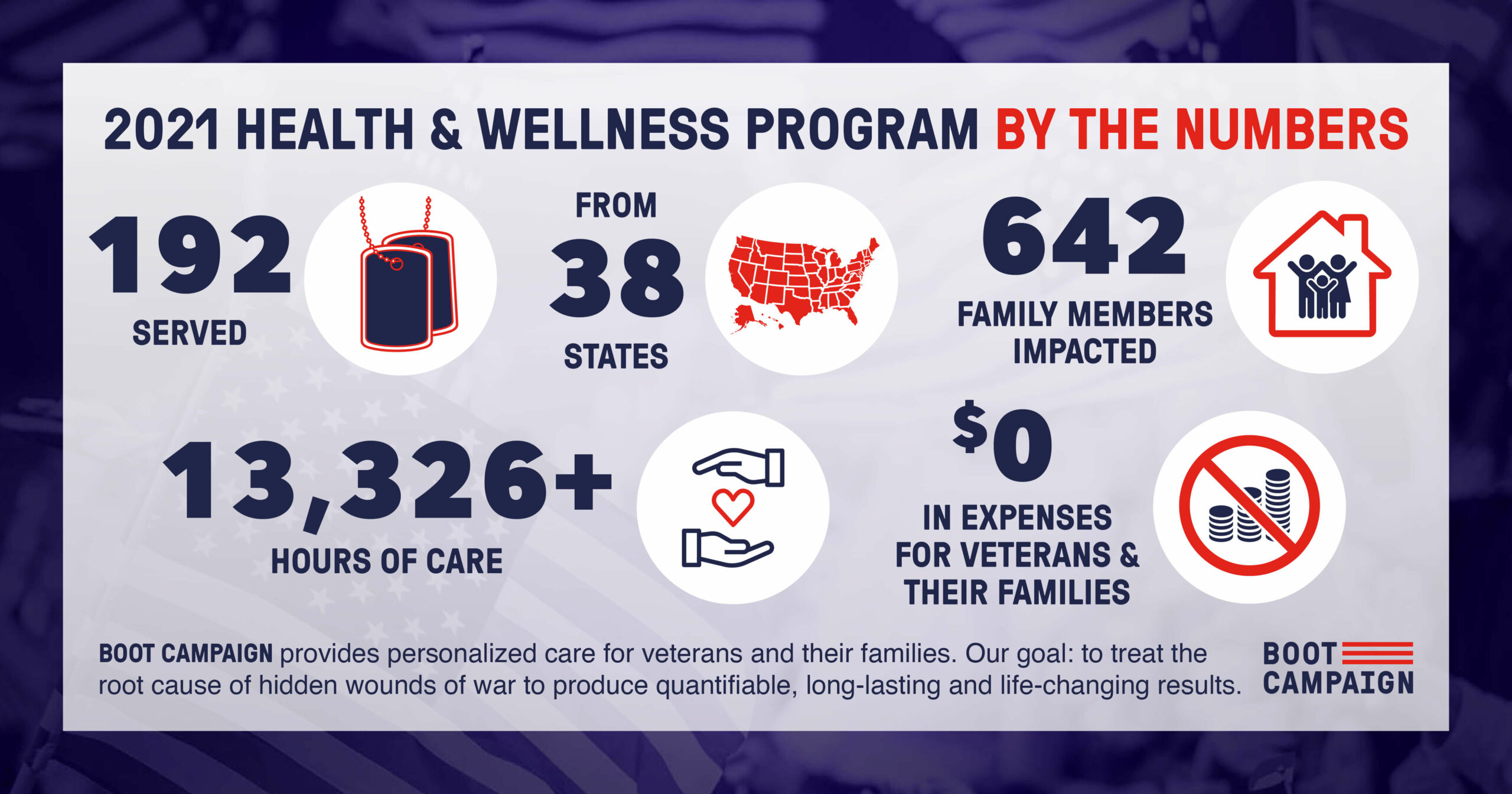

While the film’s digital medicine was mostly a welcome diversion, Byrne has found more positive and lasting results by combining “spiritual medicine” with the “cutting-edge medicine” that is customized by the revolutionary Health and Wellness Program of Texas-based military non-profit Boot Campaign.

“Dealing with TBI and PTSD has been a hard path,” admits Byrne, who stopped his unsuccessful medical care with the VA to craft his own treatment plan. “I started to go down two paths, one of righteousness and the other of self-destruction. I didn’t have emotional intelligence and, to top it off, I questioned my faith and pretty much turned my back to God.

“I was raised under two roofs, under two Gods,” explains Byrne, whose father Martin is a retired Air Force Master Sergeant and Catholic Irish Scot from Chicago and whose mother Chaubpit is a Buddhist from Thailand. “Instead of praying to God, Jesus and Buddha like I did before, I started to pray to the Holy Trinity, and Easter of 2017 was the first time I asked for Jesus to be in my life.”

Byrne’s spiritual awakening also played into his fully funded Boot Campaign treatment program when he was admitted on Dec. 1, 2017. He spent nearly seven weeks in Virginia Beach, Va., at Virginia High Performance (VHP) for intense physical testing, training and strict nutritional requirements to get his body back in shape. He then reported to the The University of Texas at Dallas and UT Southwestern for eight more weeks of treatment under the direction of neurologist Dr. John Hart, including a complete diagnostic workup of his body and brain.

“I wanted to approach this program from the ground floor up,” explains Byrne. “I told them I wanted to set up my foundation with the Holy Spirit and the Gospel, and then from there I wanted work on my body and then my mind, and it turned out pretty well. I could feel the Holy Spirit working in this Boot Campaign program.”

Byrne struggled mightily from 2011 to 2017 to find the right remedies for his war-torn body and mind, suffering through the highs and lows of countless unsuccessful treatments and medications, and wading through a myriad of potential programs that for one reason or another were not the answer for him.

To help other suffering military veterans avoid the delays and mistakes of his own experience, Byrne offers the following words of wisdom to speed up the process.

“Stop wasting your time with these other programs and get in line with Boot Campaign,” suggests Byrne, regarding the intricate four-phase treatment program that provides access to the most innovative and holistic care for TBI, PTSD, chronic pain, self-medication and insomnia. “Set up something with them and get in line now to get yourself fixed. These people are genuine, they care and they are vested.”

While Byrne feels he is finally headed down the right path, both medically and spiritually, he knows full well that his road to recovery has no shortcuts.

“I know the body you’ve got to work on every day, the mind you’ve got to work on every day, and your soul you’ve got to work on every day, so that’s what I’m doing,” declares Byrne.

“I think my wife Alma coined it the best,” he adds. “She says it takes a village to raise a child, but it takes a bigger village to bring a combat veteran home, to really bring them home, because it is a long road and not an easy one.”