Shattering Stigma of Seeking Care for Mental Health | Part I

PART ONE OF A TWO PART SERIES

In May, we marked Mental Health Awareness Month. And while a national effort to openly discuss mental health during a particular part of the year is helping to move the conversation to the public vernacular, attention to it is a year long effort and there is still much work to be done.

The problem of suicide in the military community remains on the increase. Military.com reports that the U.S. military in 2018 experienced the highest number of suicides among active-duty troops in six years. Last year, 300 Army soldiers took their own lives, bringing the number to a five-year high. Seventy-five marines died by suicide, the highest number in the last decade. Sixty-eight sailors took their last breath, a 53% increase. Twenty-two members of the Special Operations Command ended their earthly life, tripling previous years loss of life. These numbers are scary and come on the heels of the September 2018 Department of Veteran Affairs report that we’ve seen an alarming increase in the number of suicides in young veterans.

As a nation, no longer can we stand by and solely focus on awareness of mental health and suicide. Now is the time to act. To that end, we want to continue the conversation about mental health throughout the year, not just for 30 days out of 365.

I sat down with two warriors to talk about why the stigma about mental health issues exists in the military community, how they sought help and what their hope for the future holds for their fellow warriors.

During her 21 year Army career, Kelly Rodriguez deployed more than five times as a combat medic. She is married to former Green Beret Michael Rodriguez and their son currently serves in the United States Army. Kelly currently works as a benefits advisor for the Department of Veterans Affairs and volunteers for the Global War on Terror Memorial Foundation.

Spencer Milo deployed two times to Iraq and Afghanistan in service to the U.S. Army. He was medically retired in 2013 after receiving a Purple Heart for injuries sustained while conducting combat operations. Spencer is now the Director of Veteran Programs, Communications and Development at the Marcus Institute for Brain Health.

Shelly: Matters of mental health often carry negative connotations and stigmata. These views are fueled by a lack of public awareness, knowledge, and understanding of the realities of mental health issues combined with both personal and societal fear. Broadly de-stigmatizing mental health issues that may lead to suicide ideations will require a long-term sustained effort. Why do you think there is such a stigma around seeking care for mental health issues in the military community?

Spencer: For me, stigma is driven primarily from a point of misunderstanding and lack of education on what mental health really is and how common of an issue it is in all populations, not just the military community. There is definitely a large misconception of how capable a person can be even when they are struggling with a mental health condition or after treatment.

Kelly: Stigma generally comes from the idea that mental health issues constitute a weakness. When I joined the military in 1996, it was still very frowned upon to have an appointment with behavioral health experts. It wasn’t until we were well into the Global War on Terror that leadership began to address mental health with their soldiers. However, leadership was still very secretive about seeking treatment themselves.

Shelly: Did you seek care while on active duty?

Kelly: I did, and it was a tough road. The screening process was not thorough, and for nearly three years, I was continually dismissed as just having anxiety or adjustment disorder. It seemed to me because I was neither suicidal or homicidal that my issues were not being taken seriously.

Spencer: Yes and the stigma of walking into a mental health office felt no different to me when I was active or as a civilian. However, when I left the office as a civilian, I was not concerned about how my session was going to affect my job or livelihood.

Shelly: You bring up a great point. I just read a recent report that showed about 50% of soldiers and Marines in Iraq who tested positive for a psychological problem or brain injury are concerned that their fellow service members will see them as weak. In the same vein, 21% of troops screening positive for mental health problems said they avoided treatment because “my leaders discourage the use of mental health services.” And finally, at least 1 in 3 troops worry about the effects of a mental health diagnosis on their career. These seem like major barriers about why some of those those in most need of treatment will rarely seek help. What made you seek care?

Kelly: I started self-medicating with alcohol and my whole world began to suffer. My depression was exacerbated. Thankfully my husband encouraged me to seek more intensive treatment and I chose to listen.

Spencer: After being injured and told I had six months to live, I recovered and re-deployed. Then I was injured again and staring back down a path I had already traveled; it was exhausting and an even more depressing time. I hit rock bottom with everything and was severely self-medicating. I had to make a choice, so I gave myself an ultimatum: Be who I want to be for my family and myself by finding a new treatment method or take myself out of the equation completely. I am grateful I made the right choice.

Shelly: What do you hear from other veterans about why they don’t want to seek care?

Kelly: The most common misperceptions are that nothing will help or that the VA isn’t equipped to help them. I disagree with both, not to mention the many non-VA options that are available for the military community.

Spencer: Mostly it’s fear — fear of being judged, fear of being let down, fear of being removed from roles and responsibilities. I also hear from a lot of folks that they feel labeled by a diagnosis with no way of overcoming or removing the label once they are on a better path.

Shelly: What would you say to another veteran who is struggling but doesn’t want to seek care?

Kelly: I’d encourage them to talk to someone who has walked the same path and help them find the resources they need. Seeking care is nothing to be ashamed of, but refusing to help yourself is dangerous and irresponsible.

Spencer: I would ask them if they would rather take their car in for an oil change or blow a transmission. I would explain the importance of maintenance and tune ups for mental health as opposed to waiting until they are in crisis. The center of our core is a servant soul and in order to be able to take care of others, one has to be able to take care of themselves and lead from the front. I’d remind them of that.

Shelly: What needs to change to normalize (both in military culture and society at large) the need to consider brain health like we do physical health?

Kelly: I don’t particularly like the “D” in PTSD. I prefer to say PTS or PTSI, with the “I” referring to injury. If we think of PTS as an injury, versus a “disorder,” we will attack it differently. Injuries can be treated. Injuries may leave scars which are proof of healing. We need to understand as a society that treating an illness is way easier than dealing with the results and repercussions of not treating it.

Spencer: We need to shift the way mental health is talked about in this country and around the world as a whole — from childhood all the way through aging. We need to address the importance of maintaining high quality mental health in addition to physical well being. One way to do this would be to include adding some sort of screening process to basic physicals for our young so mental health is no longer looked at as specialty care.

Shelly: How can civilians and the public help?

Kelly: Understand that despite the numbers of veterans with PTSI, it does not equate to a nigh number of “dangerous veterans” on the street. Most veterans live fulfilling lives, where we continue to serve our communities. Also, please don’t pity us. Instead of making presumptions or pitying veterans with mental health concerns, share resources that are available to them to seek care.

Spencer: Civilians can help the most by acknowledging that mental health is just as prevalent of an issue for them.

Mental health struggles and the root causes of suicidal ideology know no bounds — it does not discriminate based on age, race, religion, gender or prior military service.

To make headway on decreasing the rising rate of suicide in the military and veteran population we must work together to:

- Shatter the stigma of seeking help for hidden wounds of war that in their complexity and with other contributing factors can lead to suicidal ideation;

- Encourage treatment-seeking behaviors for the entire military family and;

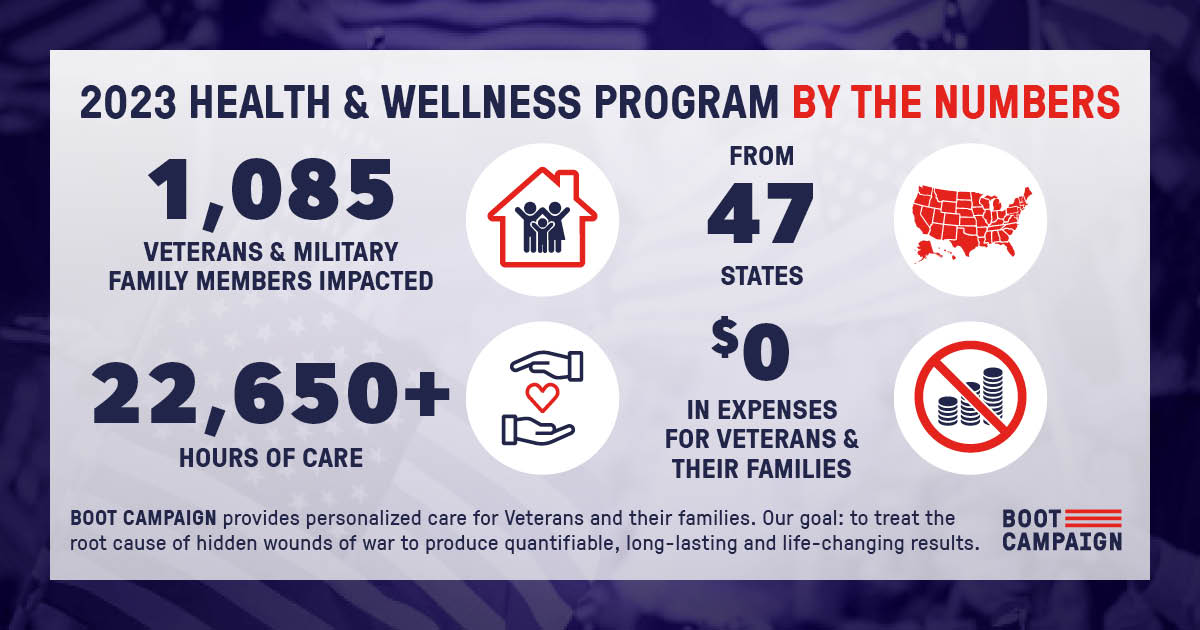

- Make access to individualized and customized care for mental health issues easier.

My next installment in this series will address the complex nature hidden wounds have on the military family.